John Richardson

(1913-1998)

4th Field Regiment, New Zealand Division

Richard in 1943 (Source: T. Caver, Dove diavolo sei stato?)

At the beginning of the Second World War, Richard, General Bernard “Monty” Montgomery’s stepson, was 25 years old, and he served as a captain in the Royal Engineers in India. In the summer of 1942 – following Montgomery’s appointment as commander in chief of the VIII Army – he was attached to his HQ as a staff officer, in charge of liaison in the western desert. «I felt inexperienced and unfit compared to the majority of the personnel, who had been in the desert for many months.»

Between the end of October and the beginning of November 1942, after the Allies reached El Alamein, Montgomery sent Richard on a reconnaissance mission in the Mersah Matruh area to find a suitable place for the HQ.

I and Lt. Col. Hugh Mainwaring[1] set out in a staff car during the night of November 6th/7th to find a suitable location. We had not been going for long when it started to rain heavily, and, unknown to us, the armoured divisions became bogged down in the desert mud some way south of the road which we were on. At dawn, there was little to be seen or heard. In fact, it was all eerily quiet. I was driving and I saw a truck with men in “coalscuttle” helmets sitting in it, whom at first glance I took to be our prisoners. But that impression quickly changed when they turned their guns on us and shouted at us to stop and get out of the car with our hands up. There was not much option. We had been well and truly ambushed, and it was a very bad moment – one of the worst that I can remember. We were put in the back of an open truck, with a big German lieutenant standing facing us, holding a pistol in his hand and were driven back at great speed to Deutsche Afrika Korps HQ.

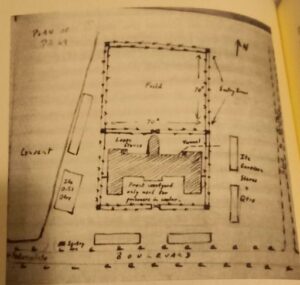

A map of PG 49 drawn by Richard (Source: T. Caver, Dove diavolo sei stato?)

During the usual questioning after his capture, no one discovered or suspected the relationship between Richard and “Monty”. During the following days, the two officers were transferred to Tobruk and, from there, to Brindisi via plane. Soon, they were taken to Bari by train and placed in PG 75 Torre Tresca, where Richard spent three weeks in appalling conditions: «In Bari, we reached the bottom.» On 30 November, with other officers, he was transferred to PG 38 Villa Ascensione (Pioppi). «It looked like Paradise compared to Bari.» He remained in this camp for six months. His final destination was PG 49 Fontanellato, where overall conditions were good, and he could play sports, walk around, take classes and watch stage plays. Here, he learned of the Armistice on 8 September 1943:

Everyone was very excited, wondering what would happen to us. Early the next morning he [the Senior British Officer] warned us that we must be ready to move out at short notice but could only take the minimum of kit and rations with us.

About midday, word came through that a party of Germans was coming out from Parma in our direction. The wire was accordingly cut by the Italian guards and we marched out into the open country. It was a strange feeling after being cooped up for so long.

In the first days after his escape, Richard remained near the camp, thinking that the Germans would focus their attention on areas further away. Like him, many other PoWs hid in a draining canal covered with vegetation about three kilometres away from the camp, often hearing the enemy’s vehicles passing nearby.

As the enemy’s manhunt slowed, Richard decided to move south, hoping to meet the VIII Army, which had landed in Puglia and was marching north. He was with Lieutenant Tony Macdonnel (nicknamed “The Dean”) and 12 other men. Richard, who knew a few words in Italian and had a map, led the group.

After a few days, however, disheartened by the bad news about the Allied advance in the south and knowing that they could not survive without the Italians’ help, they split into smaller groups to avoid arousing suspicions and have a better chance of finding some food. Richard and Tony remained together; the two were exactly 20 years apart (Tony was 49 and Richard 29).

For food, we had to rely entirely on the kindness of the peasants (i contadini), and if we were accepted at a farmhouse, they would always share their evening meal with us. This was usually minestrone and bread, occasionally accompanied by polenta (maize pudding) and a glass of rough wine. For green vegetables, they had pepperoni, which I was told by a doctor supplied all the vitamins needed. One woman, whose son was a POW in British hands, gave us two hard-boiled eggs and a small cheese to take with us on our way, but this was quite exceptional. We only had meat once or twice in the whole three months.

Unless there was fear about due to rumours of house searches and arrests, the contadini were almost invariably kind and hospitable. However, our principle was never to stay more than one night in the same place.

On 20 September, 12 days after their escape, the two reached a small village near Busana and stopped at a small inn to have some food when, suddenly, German soldiers broke into the place. They managed to flee, but they realised the danger of moving between villages had increased and thus decided to reach higher ground, following the Appenine mountains. However, the weather started getting worse during the last week of September. As they crossed the Bologna-Pistoia road, they almost ran into a German convoy.

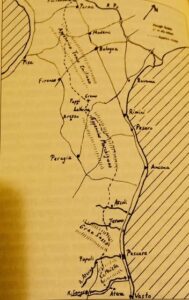

The escape route from Richard’s notebook (Source: T. Caver, Dove diavolo sei stato?)

They found shelter in various monasteries on their way, as the monks were always ready to take them in. The Eremo di Camaldoli, east of Florence, where they met Dan Ranfurly, who had escaped from PG 17 Vincigliata with Generals Neame and O’Connor; the Verna Sanctuary, from where they were able to observe their old prison camp of Pioppi; and the monastery of Fonte Avellana, under the peaks of Mount Catria.

After passing through Colfiorito in Umbria, they stopped in Castelluccio, a village on top of a hill in the middle of a large valley. Many Yugoslavian and Italian deserters lived there, which made it difficult for the two to find shelter. They marched for a few days in the chestnut woods of the area. They stopped briefly at one farm, where a woman gave them a bit of pork lard wrapped in a poster she was supposed to affix in the village. It was Kesselring’s proclamation to the population, listing the punishments – often death or the burning of one’s house – for those who had helped escaping British or American PoWs. «While she was reading [the proclamation], the shepherd’s wife started laughing and finished wrapping up our little present [the lard]. I was surprised by the irremovable courage of these people.»

Once they reached the Gran Sasso, Richard noticed that the mountain was getting heavier with snow as the days passed. Cold and malnutrition were hampering their journey and depleting their energy reserves. Moreover, they now had to cross the Pescara River, which, the Italians said, was very well-guarded by the Germans.

Near Villa Celiera, a small village, Richard ran into an old acquaintance: Major Gordon. He had escaped from PG 21 Chieti, and elected to remain in the area, sheltered by an old woman. Gordon told them they could join an Allied rescue operation, which would bring them to the port of Tremoli, already in the Allies’ hands. They agreed to send Tony with the first group, while Richard and Gordon would remain behind, looking for more escapees. After 400 miles together, Richard and Tony parted ways on 30 October 1943.[2]

However, conditions soon worsened as the Germans managed to sink the motorboat used for the rescues and attacked the harbour. Therefore, Richard decided to abandon the sea route and continue his journey on foot. At this point, at the beginning of November, snow was falling even at lower levels.

Nonetheless, Richard decided to leave his hideout with Jim Gill, a South African lieutenant he had met a few days before. They left at 5 a.m. and, at dawn, reached the dam on the Pescara river, which they crossed unopposed. They then decided to go around the eastern flank of the German army on the Sangro river.

At dawn on 12 November, they reached Roccascalena. Here, they met Donato De Gregorio, «an extraordinary man, who took us in during the following weeks at great danger for himself». Donato, who lived in Naples, had moved to the village to help his parents, who owned a farm there. Soon, Richard learned that the British had liberated nearby Atessa (about 10 km away), but the bad weather caused the Sangro to overflow, stopping the Allied advance in the area.

So, Richard and Jim remained hidden in a “cave,” a ravine between two gigantic rocks, hidden in the bushes, where they felt reasonably safe. Donato, in the meantime, regularly brought them food.

The days in the cave were very long and dreary, only made endurable by the hope that perhaps tomorrow, the Germans would pull out and we would get through to our lines. There was not much room to move around, and we lay down most of the time. Washing was difficult, and we inevitably developed lice. The only English book we had was my New Testament. Donato lent us some Italian books which I tried to read but missed a lot of the sense without a dictionary. We played various word games, and I made up a crossword puzzle.

Richard and Montgomery in Paglieta on 4 December 1943 (Source: T. Caver, Dove diavolo sei stato?)

On 26 November, announced by a series of explosions, the Germans left Roccascalena, blowing up the street north of the village.

On 3 December 1943, Richard, guided by Donato (Jim had left a few days earlier), decided to make a run for Atessa while the Sangro was still flooded. The Germans had destroyed all the bridges, but the two found a railway bridge that was only partially collapsed. The rails, in fact, were still standing, hanging above a contorted mass of steel and crushed cement. Undeterred, they decided to crawl along the rails. Finally, in the afternoon, they reached the American HQ on the outskirts of Atessa.

When I realised that I was indeed back in Allied lines, I felt truly thankful to God for bringing me safely all this way. I suppose it was about 500 miles altogether of rough going. Our motto used to be “Piano, Piano, ma Sicuro, Sicuro” (“Slow but sure”), which had paid off.

About 24 hours later, Richard was brought to “Monty” at the HQ of Paglieta. When the General saw him, he asked: «Where the hell have you been?» «Naturally, he was happy to see me but wanted to know why I had taken so long!»

Camps related to this story

Sources

R. Carver, Behind the lines in Italy. A Personal Account of my time as a Prisoner of War in 1942/3, [s.d], https://archives.msmtrust.org.uk/pow-index/carver-richard/

R. Carver, Dove diavolo sei stato? Il generale Montgomery, l’Italia e la storia incredibile di un uomo in fuga, Ianieri Editore, Pescara, 2012. Ed. orig. T. Carver, Where hell have you been? Monty, Italy and One Man’s incredible Escape, Short Books, London, 2009.

M. Minardi, L’orizzonte del campo prigionia e fuga dal campo PG49 di Fontanellato 1943-45, Fidenza, Mattioli 1885, 2015

Notes:

[1] Hugh Mainwaring’s story is available on the portal: https://www.alleatiinitalia.it/en/stories-eng/hugh-mainwaring-2/

[2] Colonel Tony Macdonnel managed to reach Tremoli on 7 November 1943. The Allied rescue operation failed, but he and the other escapees made the crossing using an Italian fisherman’s boat.