John Lindsay Alexander

(1920 – 2000)

Lieutenant British Royal Engineers

John was captured on 6 June 1944 during the battle of Knightsbridge[1] near Ain El Gazala, in North Africa.

A sorry end, but there it is […]. I do not recall ever having been so humiliated as I was on that and subsequent days. We were disarmed (at least those who had not already disarmed themselves) and pushed into column steered and controlled by light tanks (mostly the remnants of the Italian tank regiments), who did not hesitate to spray the area with machine gun fire to keep us in line.

John in 1941Source: On getting through

After only a few hours, he was transferred to Benghazi and then loaded onto the Savoia-Marchetti ship, headed to Lecce. Once in the town, he and the other PoWs were housed in the local barracks.

Later, he was taken by train to a transit camp, PG 66 Capua: «The British prisoners already there had christened it “Clickety Click” after the way the number is called in Bingo». Living conditions in PG 66 were not easy, but John seems to have faced them with resolution, as he described, in his memoirs, the various activities he took part in to fight off boredom and frustration. In November 1942, he was moved again, this time to the north, to PG 17 Rezzanello:

It was surrounded by heavy rings of wire. We could see a heap of baggage in the courtyard at the back of the building. This must be ours, we said, so this was evidently our next prison camp […].

We were told that there were two roll calls a day, a modest diet of food, and obedience to the camp guards. Nothing new, except the winter. It was already very cold in a high wind and no sign of any heating system nor logs or other fuel. […] Apart from the weather and the cold, Rezzanello was quite agreeable.

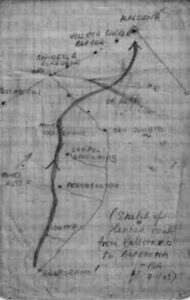

The journey from Balsorano drawn by John in his notebook (Source: On getting through

During the following months, John joined the camp’s theatre group and the library (a legacy of the camp’s previous owners) to learn Italian. At the beginning of 1943, the PoWs learned that they would be transferred to another camp, and the transfer happened in March. John was taken to PG 49 Fontanellato.

It was there that, on 8 September 1943, he learned of the Armistice. John, with some other 600 PoWs, left the camp before the arrival of the German troops, following the joint order issued by the Italian camp commander, Colonel Vicedomini, and the Senior British Officer, Hugo de Burgh. Starting from 10 September, John hid in the countryside, aided by the local population. During the day, he remained in the cornfields; during the night, he slept in the open or inside a stable.

But, where we were going? In the end we decided [John is with Jack Gatford, Michaell Lacey, John Barry] to get into the spine of Italy, to keep high up, and move as quickly as possible. We were going to be depending on finding kind peasants, getting food and direction. If we could hide up in the mountain, we would have breathing space to see if and where the Allies would land.

Thus, on 11 September, they headed south-west, crossing the railway line and the Via Emilia. By mid-September, they reached the village of Bardi, and there, they stopped, waiting for news on the Allies’ advance. The local population sheltered them, and the Italians even offered to hide them for the winter. However, the escapees decided to continue their journey with the intention of crossing the Roma-Pescara line before the first snow.

From Bardi, they crossed, with difficulty, the Cisa Pass between Emilia-Romagna and Tuscany. Then, they reached Pontremoli and climbed to the Cerreto Pass. They passed through Porretta Terme, the Futa Pass, and Barberino del Mugello. From there, they went to Florence, keeping to the city’s outskirts and the village of Dicodamo, before descending into the plains, following the Arno river. Finally, they arrived at the border between Umbria and Lazio. At that point, they decided to split to make the crossing of the frontline easier.

John and Jack then continued on their own. Near L’Aquila, they stopped in the village of Balsorano in the Liri Valley. They were sheltered in a sheep pen belonging to a local family. Each day, a person from the village brought them food, climbing the steep woods of the area. As the weeks passed (it was already December), the weather got worse, and the escapees resumed their journey. They headed to the Sangro river with the idea of crossing it. However, the path was arduous, and after only two days of marching, they were forced to return to Balsorano: «At the end of the third day, we got “home”, so to speak, and were much moved by the warmth of our welcome.»

Jack and I, rather laughing, used to say that when we were free again, we would try to raise a little monument to the Italian goat, who made little tracks through dense undergrowth, which served to tell us where the going was easiest (or at least not quite so hard) as we clambered over miles and miles of Apennines mountains. But the help from goats was as nothing to the debt we owe to the Italian hill peasant and his wife, to the farmer, the charcoal burner, who in turn saved our freedom and even our lives. This was not merely in crossing hills and rivers but eating their food, drinking their wine, and- perhaps unknowingly – bringing a sense of approaching freedom to us.

In January 1944, John and Jack resumed their journey after learning about the Allied landings at Anzio. They headed south, towards Sora, and reached Frosinone. From there, they attempted to cross the Lepini mountains. However, they soon got lost, and their food reserves dwindled. While they were meandering on the plateau, trying to find the right direction, they ran into Victor Gozzer “Tito”, an officer of the Alpini. Gozzer was a deserter and was in touch with a group of partisans who offered the escapees help, guiding them to the village of Norma, where many refugees from the Anzio area were camping.

We were escorted to a “safe haven”, which turned out to be a small ramshackle, wooden shed set against a rock face about half a mile from the centre of the village. There was an escape exit at the back. It could hardly have been better. We were then told that we would be fed and watered (which, as it turned out, meant wined) by the village, who would arrange the logistics of supplying us. Any help we could give to the residents would be very welcome: outpost, lookout, shepherding, mule-work and so on. We agreed at once and then arranged to be taught about nearby tracks, the simple protection of sheep, and keeping an eye on village livestock. We were soon installed.

As they grew accustomed to the village’s life, John and Jack became expert shepherds. Every time they wanted to resume their journey to cross the frontlines, the Italians, who had grown fond of their presence, dissuaded them.

They spent the remainder of the winter near the village, often changing their hideout as the Germans often launched manhunts to find escaped PoWs and deserters.

Only in May, as the Allies brought through the Gustav Line at Cassino, did it seem that the impasse in which they had lived was about to break. As the Germans were leaving the area on 23 May, John was told of the presence of an American patrol on recce nearby. Finally, the moment he was waiting for had arrived.

We scrambled down the hill at breakneck speed, tearing our boots to pieces as we ran. We had walked gingerly for eight months, and now, what did we care? Soles were flapping in the wind before we had done a hundred feet. As we went, we threw away the less savoury reminders of dearth.

After a few days spent on hold for identification at the American HQ in Anzio, John and Jack were told to prepare to go to Naples to be repatriated. Before leaving, they returned to Norma and Balsorano to thank and say goodbye to those who had helped them. However, they had a bitter surprise: Bolsorano had been burned to the ground by the Germans, and many of those who aided them were nowhere to be seen.

John returned home in July 1944 and in the following years stayed in touch via mail with many of the Italian helpers he had met.

Camps related to this story

Sources

John L. Alexander, On getting true-Attraversand le linee, Associazione culturale Il Liri, Canistro, 2013

Note:

[1] The battle of Knightsbridge was part of the larger fight at Gazala. On that occasion, the British forces, which had moved south to intercept the Afrikakorps, were stopped and pushed back by the Italian division Ariete.