John Fishwick Leeming

(1895 – 1965)

Lieutenant, Royal Air Force

Marshal Boyd (left) and John near Villa Orsini in February 1941 (Source: J.F. Leeming, Always tomorrow)

John Leeming was a businessman and a writer with a passion for flight. He joined the RAF in 1939 and was assigned to Air Marshal Owen Tudor Boyd. On 20 November 1940, he was en route to Malta when his bomber, shot by German anti-aircraft guns, crushed near Catania. At that point, Sicily was still in the hands of the Axis. While all seven members of the crew survived the crash, during the descent they had been forced to destroy a few boxes containing £250,000 by throwing them into the sea. The money was their bomber’s cargo and they had been supposed to take it to Malta.

Stranded in the Sicilian countryside, the men were soon intercepted by a patrol of the Italian navy, captured, and taken to Catania. John and Marshal Boyd, now PoWs, were separated from the rest of the crew and, because of their rank, housed in the Italian HQ in the city, receiving special consideration in their treatment.

I turned around and around in my bed in the dark. I used to read to fall asleep. Now, without a book, I just jumped from one of my problems to the next, and the incredible notion of being a prisoner was always on my mind. It could not be true. I heard the key rustling in the door lock. I was locked inside. I felt free to come and go only a while ago, but from now on, they would tell me what to do. There was something dreadful and inexorable in that key rustling in the door lock. I was locked inside…

A few days later, however, after a failed escape attempt that put the Italians in a bad mood, the two soldiers were transferred to Rome by train. They were housed in Centocelle, near the airfield, in a dilapidated country house guarded by sentries, where they spent some time learning Italian and plotting their escape.

It was a strange way of living. Each morning was the beginning of another day of idleness. Today was like yesterday, the same two people [John and Boyd] in the same narrow room, at the same table, the same door, the same noises, the impossibility of choosing. All that was asked of us was to stay alive and accept what others had planned for us.

In December 1940, they were suddenly transferred to Sulmona.

Villa Orsini, about one mile from the town of Sulmona, was not very large. Its architect, it seems, put a lot of effort into the decorations and the embellishments […]. However, the architect did not consider that one might want to live [in the villa] […]. Nothing was working properly. Boyd and I spent the first day unscrewing the doors […]. On the second day, we started repairing the hot water boiler and the water faucets […]. After a few days of work, Boyd claimed that the Italian government was in debt to us because of the repair work we carried out.

Villa Orsini, Sulmona (Source: J.F. Leeming, Always tomorrowi)

The following days passed without incidents. The two prisoners were allowed to walk outside under surveillance. They often ran into local farmers working in the fields during their walks. They seemed to regard the two more like “tourists” than enemies. Many of them, in fact, greeted them with a smile and a “Buongiorno”, some of them even in English, since they had worked overseas. From time to time, they received visits from other British officers held at the nearby camp of Fonte d’Amore. They, instead, were never allowed to visit the other camp.

In April 1941, while John and Boyd were on the verge of executing one of their escape plans, they were informed that a group of British generals, recently captured in North Africa, were bound for the villa to join them as prisoners.[1] The arrival of General Philip Neame meant he was now the Senior British Officer in the camp, as the 22 men were forced to live in that restrained space. «We were all active men, each with his own character. Kept idle in a small villa, it was inevitable that the nerves would get the better of us, and sometimes rage would explode..

After the generals’ arrival, we did not plan any serious escape because, in about one week, the Italians told us they would transfer us to a new, larger house. We gathered it was up north. Since that would be closer to the Swiss border, we decided to defer our escape plans until we would be transferred to our new accommodation.

The transfer, however, only happened after a few months. The group left Sulmona on 24 September 1941 and arrived at the Vincigliata castle near Florence. Moreover, a few more PoWs joined the group.[2] Split into small groups, the prisoners spent their days plotting their escape. Six of them managed to escape from the castle through a tunnel dug under the building’s foundations.[3] John did not take part in this attempt; he instead hoped to leave the camp through repatriation.

Since my plan to leave Villa Orsini using a train headed to Roma had failed, I had lost faith in “escape plans”. I had heard more than enough of them: discussed, reasoned, planned, modified, half-tried and so on. […] To me, the problem was not how to escape. […] The biggest hurdle was travelling across Italy, across the border, and entering a neutral country. […] I had no faith in my ability to run around dressed like a nun or something like that. I was a regular British businessman, and I looked just like that. […] After a week or so of reflection, I devised my plan to leave.

With the help of Neame, the other PoWs and an Italian doctor, John decided to faint craziness. He played the part by refusing food and depriving himself of sleep: «after six weeks, I was beginning to look, and feel, really ill».

On 8 January 1942, he was transferred to the Careggi hospital in Florence. He was treated by a specialist, who was an anti-fascist, and who aided him by attesting he was affected by a persecution complex. Furthermore, he required the visit of a commission to examine John for repatriation. During the following months, John continued to play his part:

Helped by the information that the doctor gave me, I showed the symptoms of my illness. […] Since I believed that the success of my plan relied on my ability to live the part, I became an anxious and whining derelict. I was a source of dread and discouragement for the Italian guards. Major Bracci was concerned I could kill myself. […] During this period, I wrote letters to the Italian authorities. They were full of clever whining. […] Ultimately, Rome was convinced and agreed to send a specialist to visit me.

The medical commission arrived at Vincigliata on 1 May 1942, eight months after the beginning of John’s plan, and they decided to allow him to be repatriated. The following six months were the hardest for him: he had to continue his façade while at the same time trying to regain some strength. In January 1943, he was informed that he and Pip Stirling would be transferred to the Lucca Military Hospital and, from there, to the United Kingdom. The moment John had been waiting for so long had finally arrived.

I sat in agitation for the following four days, making and remaking my luggage. I realised the moment had really come. I was sad to leave. I had grown so accustomed to the routine of the prisoner’s life that the idea of returning to regular life was unsettling to me. I looked affectionately at the castle, the panorama, the farmers walking by. It was hard to leave behind some of my fellow prisoners.

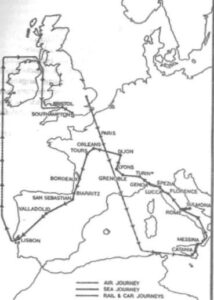

John’s journey (Source: J.F. Leeming, Always tomorrow

John’s stay at the Lucca hospital was not easy. The crumbling and overcrowded building housed more than one hundred patients with various degrees of illness. The two prisoners smuggled in some electric stoves to supplement their meagre rations and cook more food.

At the end of March, repatriation was finally approaching. John and a few other prisoners were transferred to the Lucca train station using some ambulances, and then they left for Genoa. From there, they went through France, Spain and Portugal. On 8 April, they boarded a medical ship and left the continent for the United Kingdom.

I walked quickly up the gangway, and as I felt my two feet touch the ship’s deck, I looked up – I suppose I am too sentimental – at the flag flying from the masthead. “Done it!”

Camps related to this story

Sources

P. Neame, Playing with strife: the autobiography of a soldier, G.Harrap & Co, London, 1947.

J.F. Leeming, Always tomorrow, George G.Harrap & Co, London, 1951 [trad.it], Sempre domani, Qualevita, Torre di Nolfi-L’Aquila, 2019.

Notes:

[1] They were Generals Philip Neame, Sir Richard O’Connor, Adrian Carton de Wiart, and Gambier Parry, Brigadier E.J. Todhunter, Colonel G. Younghusband, Sergeants T. Brain, H.J. Baxter, Price, and Pitt, and eight more men of lower ranks.

[2] These were Brigadiers Rudolph Vaughan, James Hargest, Reginal Miles, “O Bass” Armstrong, and Pip Stirling, Colonel George Fanshawe, and Lieutenants Victor Smith and Lord Ranfurly.

[3] These were Neame, Miles, Hargest, Carton de Wiart, Boyd, O’Connor, and Combe. A detailed retelling of the escape is in Neame’s book: Philip Neame, Playing with strife: the autobiography of a soldier, Harrap, London, 1947.