Ronald Mann

Royal Artillery

Ronald, a lieutenant, enlisted in March 1940. In August 1941, he was put in charge of a unit in the Libyan desert, assigned to carry out quick attacks against enemy tanks, despite his inexperience in warfare and weapons (something he was well aware of).

In March 1943, while he was travelling on a truck to attack a German position, his vehicle suddenly stopped near some German tanks. Ronald tried to escape but was rapidly captured.

There is no describing the sickening and deadening sensation of being taken prisoner. One minute, you are living in an active familiar world, granted a somewhat perilous one, and suddenly, within the space of a few minutes, everything is changed […]. But it is not the fact of being on the other side of the battle or of meeting your enemies that strikes you most. It is the change from action to inaction, the change from giving orders to being carried about not even ordered, but just moved like a load of ammunition or a bundle of empty petrol tins.

He was kept for about three months in a transit camp near Tripoli, where he was struck by a severe case of dysentery. Later, he was boarded onto a German cargo ship, taken to Naples, and then to PG 66 Capua. Ronald recalled this camp as crumbling and infested with insects. Immediately, he started working on an escape plan; however, after witnessing many failed attempts by his fellow PoWs, he decided to abandon it.

Afterwards, he was transferred north, to PG 17 Rezzanello, an old castle. Here, he spent his days reading, studying Italian and plotting his escape.

Suddenly, one day, we heard that we were moving, and within a few weeks, we were in another camp for 600 officers. The camp had been an orphanage in peace time and was in the middle of the village of Fontanellato, near Parma; we could watch ordinary life going on outside the camp.

Ronald recalled that PG 49 Fontanellato was well organised: «something in between a university and a monastery». Ronald took painting lessons and played some of the sports permitted.

On 2 September 1943, while he was playing football, he injured his eye and was transported to the Piacenza military hospital, where, a few days later, he learned of the Armistice. As rumours began to circulate about the impending arrival of the Germans, Ronald decided to run away, escaping from a window with his companion, Fred.

It may be surprising, but the decision to break out of prison was a hard one. On the one hand there was the safe sad world of inside, where there was at least a bed, some food and some warmth, and a certain safety. On the other there was the hazard of cold and hunger, nowhere to sleep an no certainty of security. The hold of the known and the safe is always strong, and not least in prison camp.

The train took them to Bettola, a village in the Piacentine mountains. They were sheltered there by local farmers. It was the first time in a while that Ronald could sleep in a real bed.

In his memoir, Ronald describes life in the farmhouse where he lived. He recalls the women’s subordinate role and the different foods – particularly the polenta – that the Italians offered him.

We decided to rest in that area for two or three days. The weather was dull. It was hard to realise we were living above 2.000-3000 feet above sea level. The sense of freedom which I had can best be described by comparing it with the disappearance of a toothache or a bodily pain or illness. At the camp, even when I was really fit, I always felt as if one of my faculties was missing or out of order. Now, even though I had, in fact, lost the use of one eye, I felt whole again.

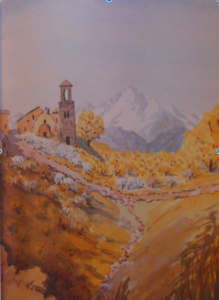

Fagnano Alto in an oil painting Ronald made after the war (Source: R. Mann, Moving the mountain)

After evaluating all their options (stay in the area or attempt to reach Switzerland), he decided to head south, convinced that the journey to the Allied lines would be easy. The weather was still fair, and Ronald was sure he would be fed and sheltered by local farmers along his way. On 13 October 1943, he and Fred left Bettola.

They marched for four weeks, covering about 250 km, but they soon realised the journey was still long, and the upcoming winter made it difficult to move across the mountains. Moreover, the Allied offensive had stopped. «However, at this point, both Fred and myself felt impelled to go on and tackle the impossible.»

Luckily, the weather remained good, allowing them to cross the Apennines through a railway gallery between Bologna and Florence. They reached the town of Prato and again climbed the mountains, passing through Mount Falterona.

As they approached the front line, however, the situation changed. They were forced to remain up in the mountains, unable to go down onto the plain. They ventured onto the Gran Sasso, covered by snow. The path was harsh and demanding. Moreover, they learned that the valley below was teeming with Germans.

At a certain point, they met a local former miner, Vittorio, who proved crucial in aiding them. He warned them about the area’s dangers and invited them to stay hidden and wait for the Allies to overrun the province. He himself built them a small cave between the houses of the small village of Frascara (Fagnano Alto), where they lived for more than three months.

Vittorio and his wife Anna were wonderful to us, bringing us food for breakfast and lunch. In the evening, we would go down to their house, which was on the edge of the hillside, for a meal with their family.

They celebrated Christmas 1943 with Vittorio and his family. On 4 February, Ronald noted in his diary that he was able to wash himself and trim his beard. Wearing one of Vittorio’s best sweaters, he went to the fair in nearby Fontecchio, even though the Germans had their HQ in the village, hiding among the crowd.

A month later, they ran into an American pilot, Roane, and this event convinced Ronald that it was time to move again. His objective was to cross the Maiella. He resumed his journey on 14 March 1944.

The parting from Frascara and from Vittorio, Anna and Elisa was rather like leaving home. Ever since I have talked about going, they have besieged me with all the reasons for staying. Everyone from the village, where we have felt so much at home, has been very kind.

Ronald Mann in uniform(Source: R. Mann, Moving the mountain)

)

The following days were difficult and strenuous since he had to move through the back of the German front line. He decided to walk at night and stay hidden during the day. It was freezing, and Ronald found it impossible to sleep. Soon, he ran out of food and water.

After a while, he joined a group of Italians, and they started climbing the Maiella, often passing near the Germans. As they reached higher elevations, they found themselves struggling with ice and snow. Often they took paths they were later forced to abandon, restarting from square one.

They learned that in Sulmona, there was an organisation that could provide them with a guide to cross the mountain. Soon, they were entrusted to one of them, Mario, who assembled a group of 17 people (Ronald, two South Africans, a Scot and 13 Italians) and guided them on a different path from the ones they had tried in the previous days: «The guides said it would take five hours from here to make the top and between six and seven hours to the other side where our troops were.»

As they climbed, the bitterly cold wind and snow once more proved unrelenting, and the group’s members suffered from sudden illnesses and collapses. In particular, the two South Africans, severely frostbitten, had to be carried by their companions.

When in sight of Palombaro, we stopped again, and one of the Italians went forward and asked a little girl who was there. British or Germans, she replied British or at least Indians, and on we went.

[…] Moments like that, a moment that I had dreamed of for two years. It was impossible for me to realise that I was free.

In the following days, Ronald was transferred to Naples and then took a ship to Glasgow:

Two weeks later, I was at last walking through the front door of my home. I must have pictured that moment of arriving a hundred times.

Campsrelated to this story

Sources

R. Mann, Moving the mountain, Aldersgate Productions Ltd, London, 1995